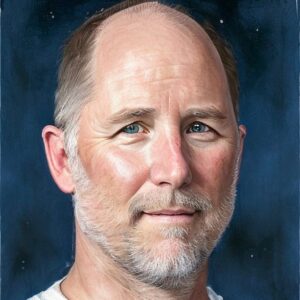

Flavin Stories is a misordered memoir.

There’s an ancient Indian parable about a group of blind men who had never come across an elephant and who are imagining what the elephant is like by touching it. Then they describe the elephant to each other based on their limited experience, and of course, their descriptions are vastly different.

I’m writing Flavin Stories as they come to me. The idea is to “feel” the tales individually in order to “see” the whole story.

Chasing My Ghost

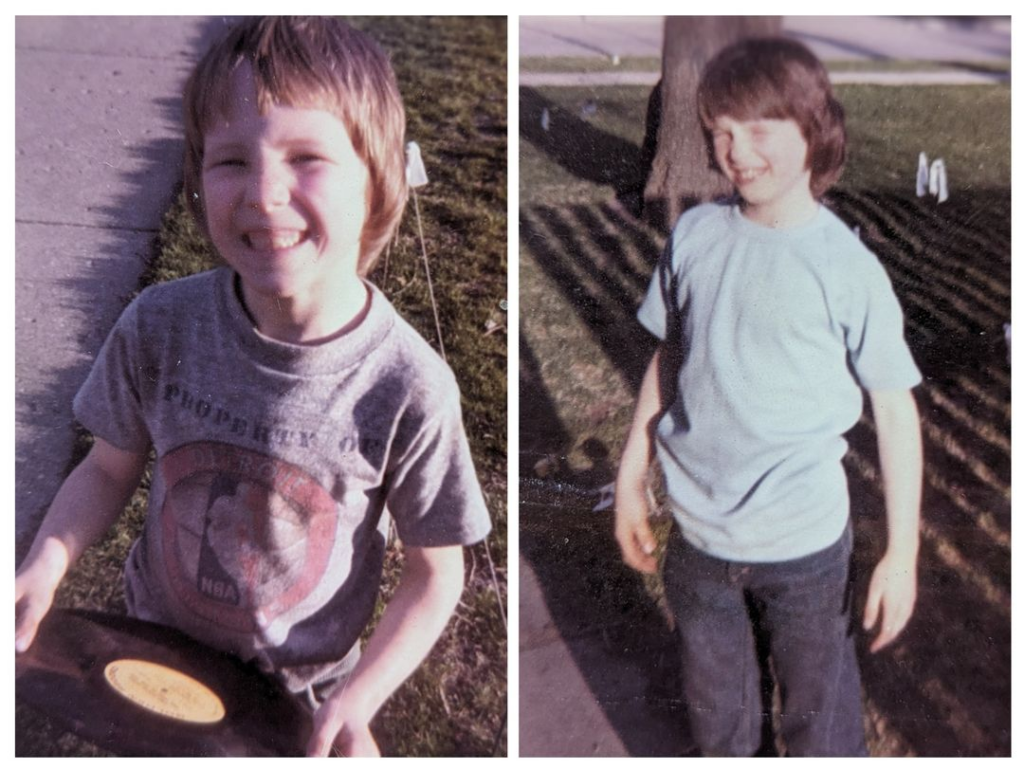

In 1974, three role models left the Flavin household, reducing our family from seven people to four. My dad, and our oldest sister and brother, for varying reasons, moved out. A single mother and three boys, ages 12, 9, and 8, remained. I was the youngest.

In 1975, I was molested. I had always known that it had happened, but for 22 years afterward, I didn’t realize it caused damage or trauma till I was 31.

In 1983, at age 16, mom died of cancer and dad didn’t fill in much as a father. He was a great guy, but parenting was never really apart of the parenting plan.

These are the main childhood experiences that shaped my life, and in many respects, who I am. Along with that, of course, I was handed plenty of good fortune and much to be grateful for.

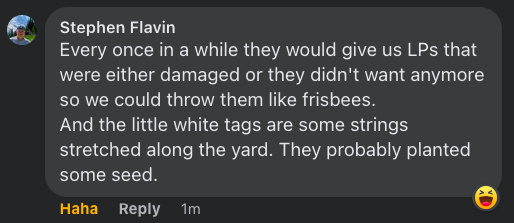

I had loving and loyal family members who knew humor, language, and music well enough to create in me and my siblings a healthy curiosity about the world. We regularly hung out with a lot of cousins, aunts, uncles, and friends with whom laughter was the centerpiece of our gatherings. I had no known disabilities, physical or otherwise. I am a straight, white, male. And, I grew up in a time when the same people lived in the same houses for decades. Whereas my family lacked stability, my neighborhood was so reliable that 45 years after moving away, I can still say who lived in most houses up and down my street, Sherman.

These are a few of the reasons I’ve been blessed.

Our neighbors included, among others, the Fitches, Lundbergs, Zielinskis, Dystants, Harrisons, Mortons, Ellers, Manners, Kulicks, Mr. Roland, Mrs. Fallon, and Crabby Appleton, who would be out her front door like a dog to bark at you if you walked on her front lawn to cut the corner. Her name wasn’t really Crabby Appleton. I don’t remember her real name.

Having predictable neighbors helps people grow up in a healthier environment, but it doesn’t necessarily make our lives more interesting. Adjusting to someone else changing residences after 10 or 20 years isn’t particularly complicated. It’s a bummer, or maybe it’s good, but either way, what are you gonna do?

Our lives are shaped by those events in which we’re too young to make sense of all the unplanned shit that happens to and around us, and usually you know as much about “complicated” as a cat watching the neighborhood through the living room window.

Twenty-two years, though, was a long time for me to be ignorant of my own prepubescent sexualization. There were consequences. Outcomes.

Dad was not a role model who offered tough love, mom wasn’t there to say “go get ’em” while transitioning to adulthood, and with my early sexualization implanting a stone of self-hatred that filled the vacancies left by relatively absent parents, my grandiose visions of self often collapsed like a well-played game of Jenga.

This is how things went for 22 years, from age 9 to 31, and for a few years after that while I re-assessed everything according to a very steep learning curve that naturally took place after my awakening.

In my early 20’s, I would drive past the University of Washington from outside the campus, see the 100 year-old buildings, and think to myself, “Everyone in there deserves to be there. They’re intellectuals. That’s not me.” I later attended U of W when I was 27 and discovered that half the student body was naive boys and girls. Not stupid people necessarily, but not blowing anyone away with their intellectual prowess either.

I sabotaged my educational trajectory, too. After high school, it took six years and five community colleges to get a two-year associates degree, eleven years to obtain two four-year degrees, and I was 38 before I earned a master’s and got a career as a teacher.

The invisible flow of low self-esteem had also convinced me I was unworthy of smart, attractive women or stable, motivated friends. The insidious part was that I didn’t view it as a lack of confidence, or even a sort of obstacle. If I had believed it were merely a wall that needed to be scaled, I might have overcome it as a matter of pride or in search of a challenge; instead, like the impenetrable University of Washington campus, it was a foregone conclusion: I simply wasn’t in their league, and I didn’t even contemplate it.

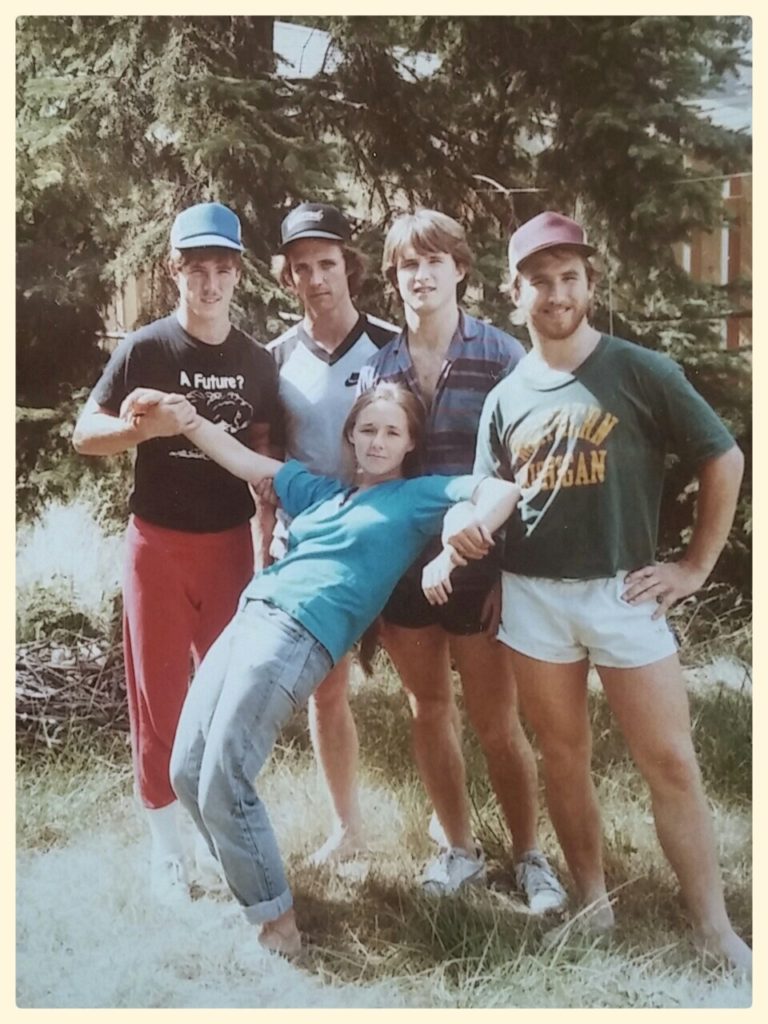

My employment, living arrangements, car, fashion sense (see photo below), common sense, and social life also weathered the same results of low expectations. Mediocrity was normal because that’s what I accepted, despite the plain and visible fact that I was capable of more.

Being sexualized before I was developed sexually created a kind of regulator in my brain that seems to have constructed inferiority (or failure) as an integral part of my self-view. I used to say I was “less-than.” The fact that I was born and blessed with good health, intelligence, an agreeable appearance, a sense of humor, kindness, and decency counted only occasionally as reasons for self-love or pride.

We all have something to offer the world, but it doesn’t amount to much if you discount it after every show of weakness.

Until I realized that everything for which I should be grateful might be discolored and burdened and sometimes entirely strangled by even the slightest defeat, my life was a seesaw of contradicting perspectives of who I was and what I was worth. Having been molested, however benign it had seemed for those 22 years, made it so that on Sunday I could believe I could be the President of the United States (literally), and on Monday, I was crumpled, sobbing in the corner of a closet (also literally).

One outcome from my delayed emotional development was my daughter, now 33. I met her mother, a 16 year-old named Diana, on a bus at 2:30 in the morning. She didn’t know that the buses stopped running for the night, and instead of letting her continue to downtown Seattle with no place to sleep, I kindly invited her to my apartment. A few months later, she was pregnant.

When I was 22, I announced the pregnancy to my family at a gathering that I had organized. My grasp of the situation was so limited that I didn’t realize the obvious: their response would be, “Oh. My. God. What the hell just happened?” Even after their decidedly not celebratory but authentically muted response, I didn’t read the room. I was oblivious.

Unsurprisingly, trying to be a father with a teen mom didn’t go well until many years later, but in the end, Angel, and our relationship, turned out to be an absolute blessing. My relationship with her mother is good, too.

When I was 31, I had an awakening. I became aware of the invisible self-esteem regulator, and the 22 years of ignorance came to a weeping halt.

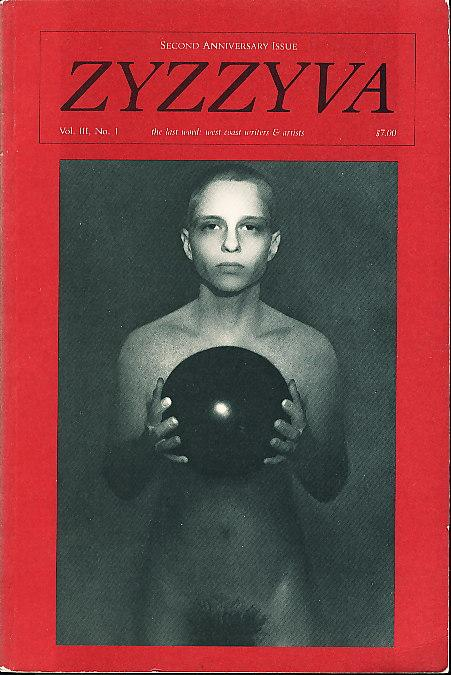

I had gone to a writer’s workshop (Zyzzyva) in San Francisco. After workshopping my satirical novel about the “one, real afterworld,” all of the participants met at a local bookstore and took turns reading an excerpt or two from our work.

I wasn’t prepared because I was still in La-la Land; I deluded myself into believing that everything I was about to read was funny or captivating and would result in the audience busting out in laughter or murmuring in awe. I had visions of myself shaking hands and smiling and spending hours that evening in conversations about my personal inspiration and future aspirations.

But no one laughed when I thought they should. No one laughed at all, or so much as chuckled or expressed sounds of affirmation. When I finished, they clapped.

My expectation was localized stardom and possibly networking with established writers, but because I had such potential for self-loathing, what I perceived was the stifling silence of rejection. Today, I still couldn’t say how bad it actually went; for all I know, it was fine.

But since my reading wasn’t hilarious, profound or intriguing. It was awkward and embarrassing for me. I believed I was a failure.

I walked out of that book store as soon as I could, not staying for the next few readers or the after-hours drinks. I went back to my motel, which had one high window and held darkness like a tomb, even with a lamp on. I cried and felt the pain of knowing that I was a complete loser. Eventually, I fell to sleep, the sun rose, I caught a taxi to the airport, and I returned to Seattle.

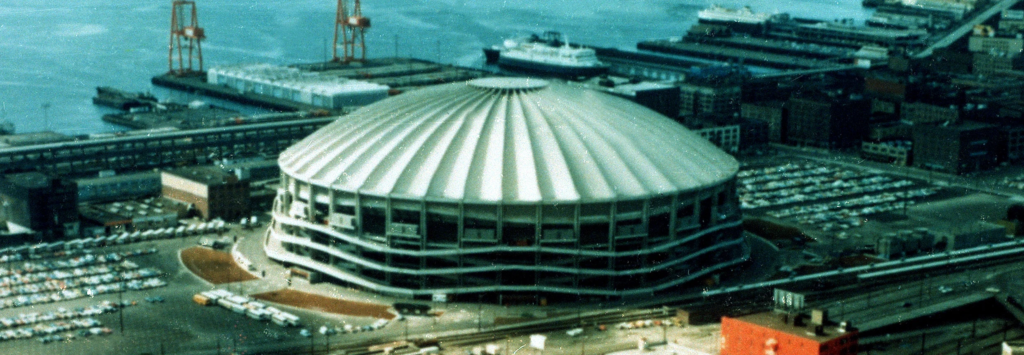

I retrieved my car from the daily lot and wandered back toward the city, bemoaning my anonymous and meaningless role in the world. I pulled into an empty lot just south of downtown Seattle on Fourth Avenue across from the Kingdome.

On the surface, I was crying because my reading had gone poorly, and it seemed to concretely prove that I was not going to be a writer at all, let alone a famous one.

Still, a voice in my head said my anguish didn’t add up. Something wasn’t quite right about feeling so much despair over a single defeat. The voice seemed to juxtapose the image of my singular reading in San Francisco next to the big calendar of life. The images signaled that my lost evening did not equate with canceling the value of my entire being since I was born in 1966 to whatever future date that I would cease to exist.

(Never mind that it was a reading in a single bookstore for participants of a single workshop that reached a few dozen people. This, too, was part of my delusions: that anything I did on that evening had much of an impact at all was an inherently self-sabotaging presumption. Now I understand that it was a night from which to learn. It was a nice start to a writing career, an opportunity to network, and it was excellent practice sharing my ideas with other writers. Then, however, it was complete catastrophe.)

It’s obvious to me now, as it should be with any rational person, but up until that moment, rational thinking was only a part-time option for me. I didn’t think of it that clearly then either, of course, but while sitting in my car, I sensed that I wasn’t lost and alone in indefinite misery. I knew there was more at play, and that’s when I decided I needed therapy to try to figure out what was going on.

I met a therapist I liked, Ron Egger. He framed things in a way that allowed me to finally hear another perspective, to consider that there might be something wrong with me that could, in fact, be changed.

We figured out pretty quickly that I was having abandonment issues and that my premature sexuality were experiences neither my body nor mind could understand. That those early childhood traumas led to a distorted sense of self. Losing my mother at a young age compounded matters, and those experiences quickly became the roots to understanding my erratic sense of self-worth.

I will always be wary of the demons born in those days because I spent 22 years not realizing they were there. They’d gotten to be crafty fellas who, even as I learned new strategies and built defenses, found fresh ways to delude me.

It interrupted my emotional maturity, distracted my common sense, and led me down too many self-destructive paths crowded with thorn bushes, grave-sized holes, counterfeit treasures, and delusion-shaded mirrors. Drugs, sex, lies, and stupidity were inevitably the tools the demons handed me so that I could sabotage whatever goodness I had earned, or with which I had been blessed.

I have been playing catch-up with myself for two and a half decades since. For the first half of my life, I saw myself flying high in the sky over all the basic people, believing my own delusions of grandeur.

Ron, my therapist, helped me to appreciate myself. Figuratively speaking, he helped me to focus so that I could see my body running up ahead of me around the track. We all have at least two parts of our selves: who we think we are and who we really are. I think we’re in a good place when the two selves become one.

I had been disassociated from the authentic John Flavin born in 1966, and if I had not heard that voice in my car across the street from the Kingdome, I might still be living in ignorance, never knowing that a real me exists, chasing my ghost.

About Memories

I’ve thought a lot about the meaning and significance of memories, but it wasn’t until I started writing Flavin Stories that it occurred to me how much a memory changes over time. When I write a story, I do my best to tell the truth. It was instantly obvious that the so-called truth of any memory is short-lived.

Memories are only static in the first few moments after the remembered event, and then they change with each passing day, week, month, year, and decade. Our new experiences, our physical and emotional maturity (or not), and accumulated knowledge reshapes the memories according to our evolving understanding of them.

Even in the moment, a childhood recollection might be skewed by other people’s reactions to the event; for that matter, one’s own bias usually changes their flavor.

We think our lives are taking a predictable path, until they don’t.

And then you reassemble. Or you re-remember. Or, you look back and figure out that so many ordinary life experiences didn’t puzzle themselves together the way you hoped they would. Or, if you’re lucky, your puzzle is built in a safe, comfortable place in which you put in the last piece a moment before you close your eyes for the last time.

I remember in 1974 (I was 8) sitting on our gold-colored couch when my parents sat us down to tell us they were getting divorced. It may have been the only time that both of them sat us down to talk. It was summertime, sunny outside, the windows were at my back, my legs were under me, and mom did all of the talking.

The discussion didn’t take long. My brothers Pete (9) and Steve (12) were also there. Brother Paul (15) and sister Liz (16) were not. Mom said they had something important to say, and then they told us.

I laughed.

Mom asked, “Why are you laughing?”

“I don’t know,” I said, and then the whole thing was over in two or three minutes.

Her question was totally fair, but how the hell did I know why I was laughing? I was eight years old. I didn’t know then, and today, I can still only make a few guesses.

In those two or three minutes, the life-changing discussion was an abstract reality in which at the time I was only aware of it being somber and serious. I recall the golden couch fabric on which I sat was a little rough to the touch, and then I laughed for reasons I didn’t understand. At the age of eight, that was about it.

If 10 weeks later I had again been asked why I laughed upon hearing that news, I probably would have had the same response: “I don’t know.”

I do know some things, though. I know that I was probably laughing out of awkwardness because it wasn’t common for our family to talk in such a deliberate way, let alone with both parents sitting us down.

Over the last five decades since, I’ve learned that my dad was seeing other women, and when mom found out, the first and only thing she said to him was: “I’ll call the lawyer,” and that was that.

Dad had accepted it without debate or discussion. If he was hoping for an easy exit, he got it, and yet, he once told me decades later that he felt disappointed by her decisiveness. Still, while he was telling the story, he seemed to admire her for it.

I also know that after dad had moved out, he paid $68 a month in child support for three children.

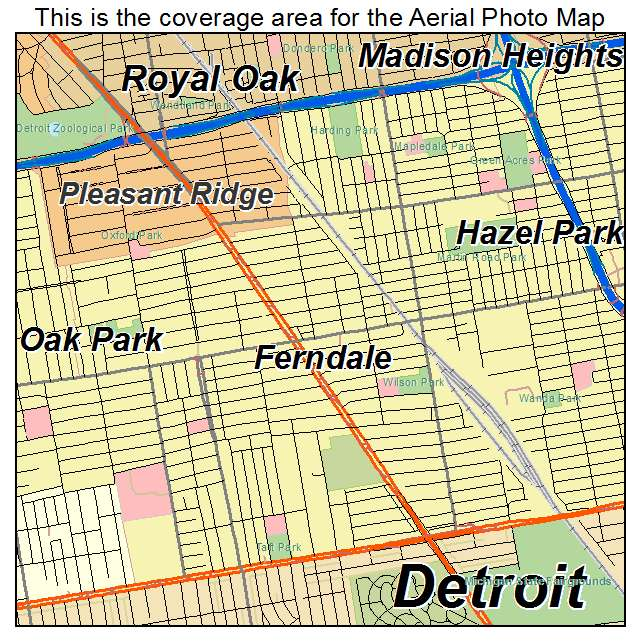

I know that, in the same year, 1974, Liz left Ferndale High School (Michigan) after her sophomore year to attend a junior college at Simon’s Rock in Massachusetts. She’s never forgiven herself for leaving mom and her three little brothers. She should, though.

I know that Paul ran away after 9th grade so he could smoke pot and drink with older friends–and escape. He recently told me that he feels guilty for defying mom (who was a pretty reasonable parent) and for not helping out more when she was dying of cancer in the early 1980’s, but he did come around quite a bit to cook mom meals. When I pressed him on what he was thinking and why he ran away, he said he’d rather not talk about it.

I know that those two or three minutes of somber discussion in 1974 gouged a gaping hole into the hull of our family at 23111 Sherman in Oak Park, Michigan. In a relative instant, seven became four, as three of us dived headlong through the opening.

Now, I know exactly why my mom asked why I was laughing.

We like to call these “transformative experiences,” from which we hope to learn, grow, and heal. Growth was easy when I discussed it many years later in the comfort of my therapist’s sofa. There, transformative experiences were neatly packaged events from which I could carefully peel off the tape, empty its contents, and contemplate whether to cry, shout, or sigh a sigh of deep relief.

And if I didn’t like the way it felt, conveniently, I could leave and avoid it for another week.

I don’t mean to diminish the value of therapy: everyone should go. In fact, my having gone was one of those transformative experiences. I sobbed, shouted, and even smiled regularly in the immense relief that I wasn’t as complete a loser after all, as I had previously believed.

When I was eight and mom and dad said a few syllables about dad moving out, I couldn’t have known that I was being tossed into the Sea of the Unknown and would fend for myself from the age of 16 after mom died a few years later, and be swept straight into adulthood.

Prior to the big discussion, I had never heard them argue or yell at each other, and then, without much urgency at all, they gathered us for a calm and collected family discussion. The announcement was so composed and painless in those two or three minutes, I probably thought it was as temporary or reversible as rearranging the living room furniture or getting a new used car.

As kids, the true gravity of these types of events often float right over our heads. As we age, we slowly begin to comprehend their value in terms of their impact on the course of our lives and meaning that some decisions hold, may it be loss and grieving or gain and celebration. How much to grieve or celebrate depends on so many factors, most of which an eight-year-old can’t fully appreciate.

I couldn’t, anyway.

I am writing Flavin Stories to tell of those transformational failures and successes–one at a time. I hope you enjoy them.

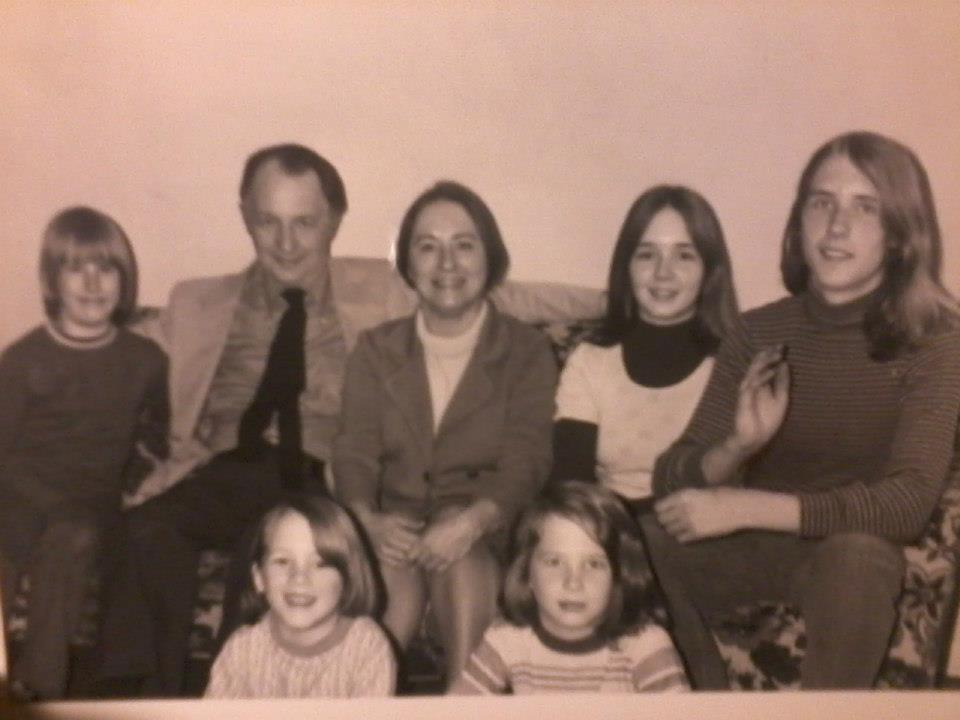

(L to R) Front: John (6) & Peter (7) – Back: Steve (10), Dad (44), Mom (42), Liz (14), Paul (13)

“My story isn’t sweet and harmonious, like invented stories. It tastes of folly and bewilderment, of madness and dream, like the life of all people who no longer want to lie to themselves.”

> Herman Hesse <