This website is mostly devoted to Flavin Stories. Above, you’ll see a number of menu options, such as Real News, Social Commentary, Academic, etc.

1,978 words, 10 minutes read time.

One-word Rule

I’d spent my 20-year high school teaching career with a simple classroom rule: respect. Every year, teachers were asked to go over the major rules in the first week. Students hated it because it’s the same thing every year. I hated it because it’s the same thing every year, and I figure they could use common sense. I know that’s a big ask from teenagers, but I took my chances and learned that they knew what to do and what not to do. Most of the time.

I started my career teaching at Molalla High School in Molalla, Oregon. There are no pure-blood Molalla Indians left, the town is 94.5% white1, and, predictably, hunting and fishing are typical pastimes there. It wasn’t uncommon to see a few cowboy hats. In 2006, a lot of students thought it was silly they couldn’t keep rifles on a rack in the back window of their pick-ups. The district is southeast of Portland and about 15 miles into the country.

Students rarely cursed in the hallways during passing time, and if they did and got caught, their eyes would go wide and they’d sheepishly apologize. More recently, I taught at Overlea High School in Baltimore County, students swore so routinely that asking them to stop was futile. If only a couple students were walking the hallway, depending on the severity of their language, I might have asked them to watch it. Genitals mentioned, a hard no. Shit, ass, or hell, it wasn’t worth it. Even fuck got a pass if it were used lightheartedly, as in, “I couldn’t fuckin’ believe it.” But if they said it sexually or aggressively, then a “C’mon, fellas” would usually evoke a “My bad.”

By comparison to the neighborhood surrounding Overlea, Molalla was a middle class town with middle of the road poverty, addiction, and abuse problems. It happened, of course, but mostly the kids were well behaved in spite of their personal problems.

When I explained my single-word rule to them, I might call on a kid I knew felt comfortable speaking up. “Kyle, is it respectful to leave the room while I’m trying to explain something to the class?”

“No.”

“And why not?”

“Because it’s rude.”

“Not complicated,” I might have said. “And how about if you have to go to the bathroom? Is it respectful for me to tell you that you can’t go?”

“Well, if I really have to go, I’m going. But if you’re teaching, I should wait till you’re done, and then ask.”

“Right. In the same way that if you were up here talking to the class, I’d try to wait till you were done.”

Then I might ask Angela about a different scenario: “Angela, if you use my microwave and your spaghetti with red sauce explodes because you cooked it for too long and didn’t cover it, what’s the respectful thing to do?”

“Clean it up.”

“Thank you. Again, not complicated. You all know when to talk quietly or not at all. You know that you shouldn’t insult people, and you know you should throw your wrappers into the garbage instead of making me clean it up.”

The word respect uncomplicates matters because everyone knows when respect happens or doesn’t happen. Even if a student believes he or she was being appropriate, or more likely, “What’s the big deal?” the conversation about what happened can be framed by the measure of respect, so it doesn’t take long to agree on where the fault lied.

Dylan

In practice, boundaries still got crossed. In 2007, during my third year teaching, Dylan sat at the front of the class. He was vocal and had no trouble speaking his mind. I was still new, so I wasn’t aware that students would ask teachers questions to keep us talking in the hopes of running out the clock and avoiding class work. God knows what we were talking about that day, but Dylan, a regular contributor, was starting to become agitated. He abruptly ended what I thought was a minor disagreement by bursting out, “Suck a big one, Mr. Flavin!”

The room went silent and became still. The other kids’ heads turned from Dylan to me. That kind of talk to a teacher was not common at this nice, average-sized, rural school in Molalla, Oregon. I’m sure they’ve all seen a few things in school, but they likely hadn’t seen that.

Dylan, a junior at the time, was 2-3 inches taller than me, a wrestler with a ton of energy, and he had braces and acne to punctuate his adolescent face. Because Dylan was so far over the top, I had a sort of instant and antithetical reaction. Having driven a city bus in Seattle (Metro Transit) for nine years prior to teaching, his outburst hardly felt like a threat. It was as if I were watching the situation from a camera in the corner of the room. After a short wait, I said, “Seriously?”

The ensuing silence swallowed him up and forced a perceptible, reluctant smile, braces gleaming, and then he quickly dug in his heels, making his case loudly without yelling. I listened, other kids started to smile, and eventually, he apologized.

They don’t teach us how to respond to this kind of hostility in graduate school, and I was still new to classroom management in a fairly tame environment, so my tools to respond were limited. The only thing I could have done that would have been wrong is show that I was effected by it. I responded similarly to how I did when a wealthy-looking woman had threatened bodily harm if I insisted on making her pay for her bus ride. “Ma’am, the downtown free-ride zone ends at 7 pm. It’s 7:30.”

“Listen, I have plenty of money. I’m only going across town. I’ll stuff a hundred-dollar bill down your throat I have to.”

“Yes, ma’am.” The official Metro Transit policy was to not dispute fares under any circumstances, so I learned to let it go, especially if they were hostile. After nine years of learning that lesson at all hours of the day and night in Seattle, that was my first instinct with Dylan. The difference between the woman on the bus and Dylan is that I had to face Dylan a hundred or more times in the next few months, so it was far more important that I remained calm. Being in a tame rural school and Dylan having been ultimately a good kid, it was unsurprising that that was the last time he and I had that level of conflict.

The one-word rule ameliorates most conflicts–so long as I stick to it.

In Baltimore, eight years later, I didn’t stick to it.

From a Rural West-coast Town to an Urban East-coast City

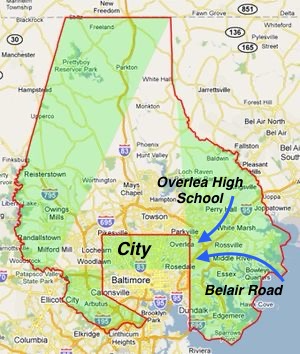

I taught sophomores and juniors at Overlea, a high school situated right at the city line and, importantly, on the Baltimore County side of that line. Unlike any other big city I’ve visited or lived, Baltimore City doesn’t share space with a county. Seattle is in King County, Detroit is in Wayne County, and so on. The City is shaped roughly like the state of Nevada, and Baltimore County is massive and wraps around three sides of it, resembling a large wrist and hand reaching down from Pennsylvania.

Baltimore City has abysmal roads with tire grooves from years of neglect that are so deep you would trip over them if you weren’t careful. In the County, the roads are pristinely maintained. If you drive on Belair Road southbound from the County to center of the City, the evidence of white flight and redlining are as plain as day. It reminds me of the 1984 film by John Sayles, Brother From Another Planet, where the mute, black main character, “Brother”, is engaged by a white earthling on the subway. The white guy shows him an elaborate card trick, and before deboarding, he says, “I have another magic trick for ya. You wanna see me make all the white people disappear?” The train, heading downtown, stops as the announcer calls out the “125th Street Stop.” The doors swoosh open, the white people deboard and people of color board. Before stepping out the door, the white earthling says, “See? What’d I tell ya?”

If you headed toward the City on Belair Road, the forests and parks become fewer and fewer, and the thriving businesses and homes are increasingly boarded up. The alleys become less traversable, and trash begins to litter the streets. The mostly white people turn almost entirely black and brown

Overlea High School is a mix of white kids whose parents have lived in the County for generations, black and brown kids who either already lived there or whose mothers (and sometimes fathers) recently moved to the County from the City. At the time I taught there, it was about 70% black, 15% other people of color, and 15% white.

It was the first time I had experienced white people in the minority. I noticed that the few white kids were mostly subdued and withdrawn. The boys, especially. What a difference that made compared to the mostly white population I taught in Oregon. There were not many overt racist acts at Molalla High School because the kids are more socially motivated by obedience, and since bigotry of any kind would stand out. Even those who had racist childhoods, of which there were plenty, didn’t want to make a scene. The other 10% were mostly Hispanic, and there were no more than two or three black kids at the school, and sometimes one.

At Overlea, being at the City line, students appeared and disappeared and sometimes reappeared to and from their desks all year because Overlea was and still is a transitory stop. Parents in Baltimore City often relocated to the County for what they hoped would be a better, and safer, education; meanwhile, other families regularly moved away from Overlea and deeper into the County, also in search of America’s promise.

Deon

It was my first year there, 13th overall. I was in the hallway briefly conferencing with another student about her attendance, and when I went back in the classroom, Deon was entertaining the others, standing in the middle of the classroom. He was looking at his phone and describing a meme about female genitalia to the other students. Everyone laughed, as I entered just in time for the punchline — and the most descriptive part.

“What the hell are you doing, Deon? Are you serious? You can NOT talk like that!”

“Aww, c’mon Mr. Flavin,” he replied, minimizing, grinning. “They’ve heard a lot worse, believe me.”

He was right of course, with the Internet and social media being what they are, and yet the sight of his half-mouth grin made its way under my skin. What added to my fury was that he didn’t acknowledge how inappropriate he had been. I had that feeling you might get before you do or say something you know you shouldn’t.

As Deon wandered toward the front of the room, which was not the same direction as his desk, I grabbed him at the elbow as if to redirect him to the door so we could have a talk. This is a line that teachers are not to cross, ever, except for safety reasons. Brows deeply furrowed, in a small sort of shock or surprise, he fiercely twitched his arm out of my grip, which reminded me that he was all-league linebacker and wrestler. I let go and was about to tell him to leave, but Deon walked out on his own volition, cursing under his breath.

I broke the one-word rule, the golden rule. I disrespected a student.

Distraught, I turned to the rest of the class and gave them something to do on their own. Or maybe I didn’t say anything. They stayed quiet, though, sensitive to the situation.

I went to the door to see if Deon was hanging around. He was down the hall, about three classrooms away, venting to his football coach (also a teacher). I welcomed him as a go-between even though I didn’t know him very well. I walked over and joined their spontaneous hallway meeting.

The coach supported me as well as he could, but Deon wasn’t having it; he was not going to apologize or even look at me. He repeated, speaking to his coach, “He grabbed my arm! Mr. Flavin grabbed my arm!” With nothing resolved, the coach took him into his room, what we called a “buddy room” when teacher and student can’t make peace.

I didn’t see him back for a week. When he returned, I tried to talk to him, but he was shut down.

A few weeks later, while trying to motivate the class to keep working hard so they could graduate (a fairly regular conversation), I weaved in my “respect as the class rule” bit and openly acknowledged my mistake with Deon a month before. I said, and I’m paraphrasing, “Even though Deon was totally inappropriate that day, I was wrong for grabbing his arm, and I’m sorry for that.”

For a brief moment, Deon and I were tethered by eye contact, which, like Dylan 11 years before, evoked a barely noticeable grin from him. From that point forward, he and I were good. He had forgiven me.

I had openly respected Deon, affirming his dignity in front of his peers, and he accepted it. I didn’t understand at the time, but pride in Baltimore runs extraordinarily deep. That isn’t to say the kids in Molalla didn’t have pride, but at Overlea High, snitching and disrespecting were sins number one and two. I made the mistake; therefore, I was obligated to surrender. It made no difference that I was the teacher and he the student, or that he originally created the problem by describing the obscene meme.

Another month later, overcoming limited interaction, it was behind us.

Respect is universal because it’s at the heart of every golden rule, religious or otherwise. My students come from everywhere, both in Molalla and Baltimore. I can’t possibly know where their shoes have been, so the one-word rule unites us. We all get it. And, because of addiction and poverty and a host of other reasons, many students don’t respect at home. To get it from any adult is welcomed, even though some of my students never let on that they appreciate it. I’ve had students remain sullen the entire school year, ignoring me or putting their heads on their desks. They might hardly say a word to me for the nine months we spent together who nonetheless come out of their funk the next year and act like we’re old friends.

I’ve long suspected that there must be something deeper than abiding by a one-word rule. Respect is universal, sure, but I tend to be suspicious of anything that’s overly simple. It also seems so easy to do: just talk to them like I would adults. That isn’t to say I haven’t been lured into power struggles, or that I’ve always spoken to students kindly. I have a Michigan sarcasm streak that was conditioned into me as a child, and sometimes my incredulity at the child’s behavior gets the best of me. But when I calm down, I apologize in the same way I would to an adult.

My suspicion that it can’t be as simple as a one-word rule was not unfounded. While preparing for a curriculum I hadn’t taught before, I read the 1993 novel by Ernest J. Gaines, A Lesson Before Dying. It consumed me and led me to understand that respect is only the action taken, but it’s what happens when that action is consistent over an entire school-year.

The story is about a childlike black man (Jefferson) in the 1940s who finds himself in the wrong place at the wrong time. He is sentenced to death row for a murder he didn’t commit. Already poor, uneducated, and possibly intellectually limited, his own defense attorney relentlessly equates him to a hog in order to argue his innocence, claiming that he didn’t have the intellectual capacity to plan the alleged triple murder. His godmother, Miss Emma, urges a young black teacher, Mr. Wiggins, to visit Jefferson at his jail cell to help him feel like a man before being executed.

In the story, being Black in the 1940s, Jefferson’s execution is presumed; she wants him to die with dignity.

As I read the story in 2020, my mind was heavy with the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor, as well as the subsequent protests and the Black Lives Matter movement. Gaines uses Jefferson to illustrate that dignity is one of our most basic human needs.

Gaines helped me to see that dignity was at the root of my students’ needs. Whether they were white in rural Molalla, Oregon, or Black in urban Baltimore, dignity was that “something deeper” my students needed.

I was overwhelmed with this sudden awareness when I read this excerpt from Gaines book, written by the inmate Jefferson in a notebook given to him by the teacher Mr. Wiggins as he begins to gain confidence:

“Im sory i cry mr wigin im sory i cry when you say you aint comin back tomoro i cry cause you been so good to me mr wigin and nobody aint never been that good to me an make me think im somebody.”

It’s not an apples-to-apples comparison, considering the story has Jefferson living in the 1940s, is on death row, and has zero formal education. Yet, at its center is a need for a humanity that transcends absence of a perfect comparison: dignity is essential.

I felt this truth being at the root of my students’ needs—children!—and as I held the book in my lap, I wept.

I wept because the falsely accused Jefferson is convinced he isn’t worthy. I wept because Jefferson is a symbol of the millions of falsely accused Black Americans during the 1940s, when Gaines’s story takes place. Of the last 400 American years, and with increasing visibility, in 2020.

Jefferson isn’t just a literary symbol for unknown numbers of unknown people, but Jefferson is my student. All at once, he became both the abstract dread about the fictional and nonfictional past and the concrete reality of real flesh and blood people in the present. Today.

As I sat with the book loose in my hand, I saw Michael, Khalil, and Taniya asking questions, writing paragraphs, trying hard. I saw Myoni’s and Kayla’s empty desks — again. I saw the smiles and the tears and heard the laughter and quarreling. I’ll always remember Kevin, not depressed today, but perpetually out of his seat. And Cameron, who could answer complex open-ended questions that no one else could while he texted a friend.

Suddenly, Jefferson was America’s Black population in the past, the 1940s, in my classroom, and inevitably, the future. I’ve always known this intellectually, but there, in that moment, an enveloping gust of tangible realness overcame me with a comprehension I hadn’t previously felt.

I wept because Gaines successfully led me — a white person — to the outside of the big and increasingly transparent snow globe that surrounds the black experience. His novel offers a close-up view of the ceaseless and pervasive truth, and I didn’t just understand it intellectually, I felt it as much as a non-black person could. Or at least as much I could, which was more than I ever had.

I cannot know from the outside of that globe. But, with my heart, my senses, and my words, I can glimpse, listen, and honor the dignity of the people living on the inside.

Today.

I began my teaching career ricocheting from one classroom management strategy to another until, out of necessity and teacher survival, I narrowed it down to the one-word rule. I wasn’t fully aware of why it mattered, per se, but eventually I found that my relationships with the kids were always improvable, so long as respect was the primary commodity we exchanged.

1 According to the 2020 census.

Written December 12, 2020