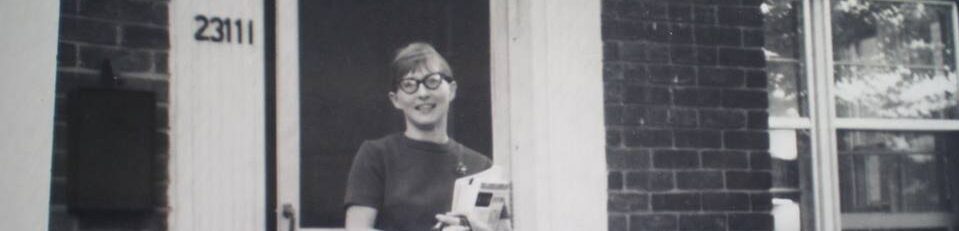

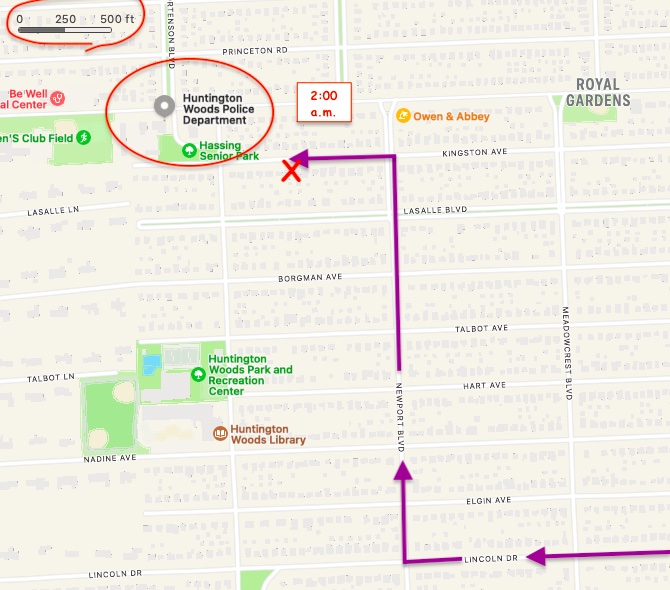

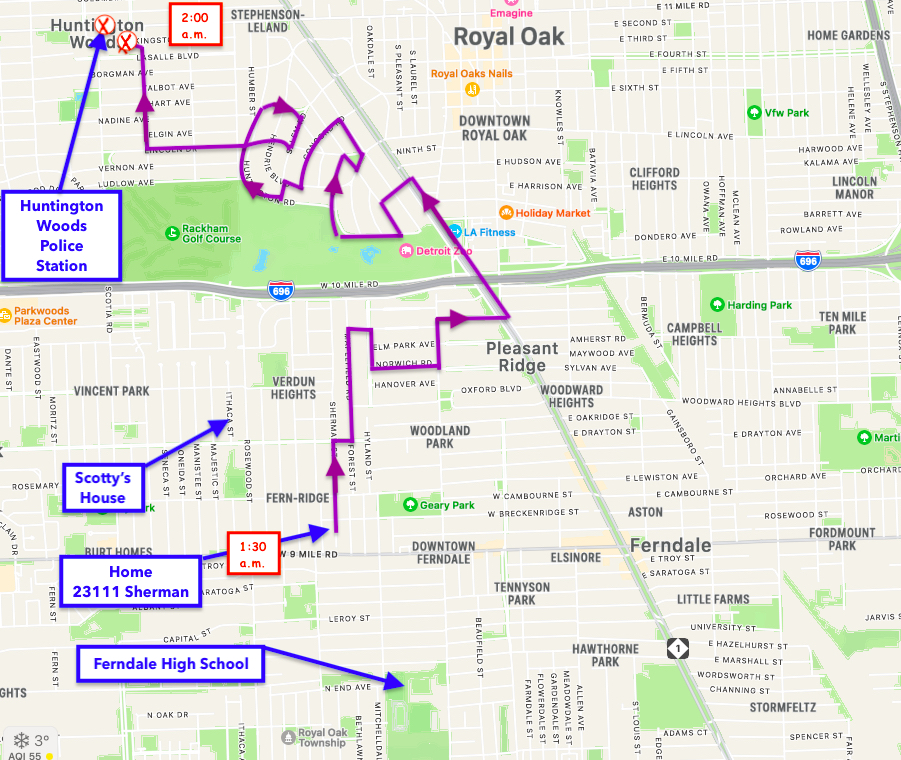

It was after midnight, and Mom finally went to sleep. My brothers were elsewhere, and my relatively new friend Scott Hurt and I decided that we’d lift my mom’s car keys and go for a bit of a drive. We were 15 years old and capable drivers without licenses or permits.

At around 1:30 a.m., we tip-toed out the front door. Scott put his hands on the hood of the car and prepared to push the car backward, and I opened the driver’s side door. I got in, put the keys in the ignition, and turned it far enough so that I could pull the column shifter into neutral but not start it. No lights.

I lifted my foot off of the brake. There was a slight backward incline to our driveway which helped us get it out of the driveway, but this was in the flat State of Michigan, so once we were in the street, we would toil to get this car moving–especially without power steering.

The car was a 1974 Chevy Malibu sedan that also didn’t have power brakes or air conditioning. Or FM radio. Granddaddy, my mom’s dad, gave her the car. It was the bottom of the line. Granddaddy was the kind of guy who literally saved his money in a mattress and was 26 with five children and another on the way when the Great Depression started. Mom accepted the gift, of course, because free was free, and raising three children with an average net child support of $26.67 per child per month sometimes required settling for less than optimal.

With Scott pushing, I opened the door, got out, and pulled backward on the steering wheel to help roll it slowly and soundlessly into the street. We had to get it fully out in the street, or else we risked it settling between the driveway and street, half in and half out, thus, forcing us to start it only a few feet from where mom rested her head. Two boys weighing no more than 280 pounds combined were not going to move a two-ton chunk of iron without gravity on our side.

Plus, a steering wheel of any 4,000-pound car that’s not running — and which also rested mercilessly on grippy rubber tires — will not turn without immense effort. Once it moves faster than 5 mph, or is powered on and has power steering, then turning becomes manageable.

So, while backing into the street, I heaved on the wheel to turn and position the car on the street. I hopped back in so I could use both arms to straighten out the wheels, parallel to the curb.

Scott ran to the back, and together, like oxen on uneven ground, we plodded forward four or five houses down Sherman Street so that mom wouldn’t hear the 8-cylinder engine banging to life in the silent summer night. We communicated without a sound, as if we’d done it a dozen times.

If a neighbor happened to look out their window at just that moment, they’d have seen two boys bounding into a dead car. They’d have heard two doors close lightly and the engine start up. They would have seen the brake lights illuminate, then off again, and then they’d watch the Malibu move slowly forward for about three or four more houses. The tail lights would turn on, and we’d fade out of sight.

We had no specific destination, so for a little bit, we focused on not looking like kids driving the car. We watched for the cops and randomly decided where to go. We avoided big roads, but we were set on Huntington Woods, so we ended up on multi-lane Woodward Avenue for about a half-mile, as we had to go around the Detroit Zoo to get there.

We could have gotten there by going around the Zoo in the other direction, but then we would have had to go through Oak Park, and Scott wasn’t having it. We went to Huntington Woods because we believed we were less likely to be seen by cops or people we knew, particularly his father, who was an Oak Park policeman.

Scott insisted, “We ain’t going through Oak Park. My dad’s not on a shift, but you can’t be too careful. I can’t take that chance.”

I’d already known Scott for a few years as more of an acquaintance from junior high, and our friendship started like any other in high school: we got to know each other better in some classes, had a few laughs, and then eventually we hung out outside of school.

We also wrestled in 9th and 10th grades. We were an even match, so the contests continued after we left the mats and the school. We’d often find ourselves grappling on other people’s lawns or in the park on our way to a friend’s house or the store or Taco Bell for two bean burritos with no onions–the cheapest buy with the most volume.

Scott and I liked to talk about the existence of god, the meaning of life, our relationships with family, and girls. While we obviously talked about girls and made typical crude sexual comments, girls generally weren’t our focus.

As we drove through Pleasant Ridge, we could relax a little: no moving cars, side streets, and it was familiar to us. It didn’t take long to get into a meaningful conversation. Ironically, we would just as soon had pulled over so we could chat without worry. I remember Scott talking about his relationship with his dad and brothers, but rarely did his mother come up.

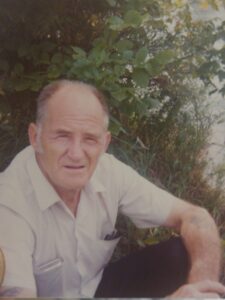

I didn’t know much about his relationship with his father, except that Scott was both troubled and proud of him. I’m not sure he knew how to feel, but one thing I understood was that Officer Hurt ruled the house, and there was little doubt about that, which was very different from my home.

At the time, I was still under the spell of my own family dynamics, which was simultaneously anti-hyper masculine, thanks to mom and dad, and bullshit macho masculine, thanks in large part to our oldest brother, Paul. Because of my parents, though, I never completely took to Mr. Hurt. He seemed like the kind of guy my they wouldn’t like at all.

My dad, for example, wasn’t exactly feminine, per se, but he didn’t care for football (or the prospect of feeling pain or being competitive) or working on cars (or getting dirty), and he hated John Wayne and wasn’t a fan of Muhammad Ali. When I got older, I was able to understand that John Wayne was a paper figure posted on TVs to titillate people’s base need for manliness and cliché heroism; whereas Ali, it turns out, was a smart, complex, and whole person not playing the part of anyone but himself. My dad wasn’t a fan of him because he got into a ring and punched people in the face and, of course, boasted a big game – all of which contradicted my dad’s tastes. Eventually, I figured out that Ali was a man of substance and my dad was wrong about him.

Therefore, my vibe on Mr. Hurt was a little uncomfortable. He was a cop, and it’s safe to say that his life preferences contradicted my dad entirely. As a police officer, it wasn’t much of leap to assume that he was capable of physical violence. Mr. Hurt was inevitably squeezed into making onerous decisions, carried a firearm (and knew how to use it), and he embraced hard work. My dad was a self-proclaimed hedonist; he hated hard work.

When I looked at Mr. Hurt, who was always pleasant enough to me, I saw a somewhat wound up and serious man with a strong and roundish body held tight by his flak jacket and uniform, and whose mustache was neatly trimmed on his otherwise clean-shaven face. I didn’t really know him, honestly, and for all I knew, he was a terrific guy. But compared to my father and his domain of conflict-avoidance and low expectations, Mr. Hurt came from the unfamiliar rugged land of manly men and discipline.

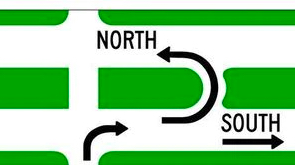

Scott and I paused our conversation as we approached the 8-lane road, Woodward Avenue, because we would have to execute a “Michigan left turn,” which meant we had to turn right in order to go left.

Scott did a lot of talking because I was driving and, generally speaking, I avoided talking about my deeper fears. Instead, I skirted vulnerability by listening to someone else’s fears and then helping to hammer out what it all might mean. I stuck to abstracts and theories and concepts, as it was a diversion that worked to keep me safe in many friendships simply because I was good at it.

Once Scott and I became aware that we liked talking about deeper subjects, we’d get into it by walking around our neighborhoods or sitting around my house since my mom worked late.

At the same time, we were both light-hearted trouble-makers, which just means we might soap car windows on Devil’s Night or swim in a lake past curfew or, possibly, take my mom’s car out for a drive. It was predictable teenage stuff that generally didn’t harm anyone.

We finally relaxed, and before too long, we made it to the relatively upscale little neighborhood that was separated from ours because it bordered the long fences of the Zoo.

We had escaped the bright Woodward lights and high-speed (45 mph) traffic. After doing a few random turns and roundabouts in Huntington Woods, we wanted to concentrate on the conversation, so we drove around, looking for an inconspicuous spot. We looked ahead and saw 11 Mile Road, so we plotted a stop on this side of it. It was a major thoroughfare, too, so our plan was that, after we talked for a bit, we’d never cross 11 Mile, and then head back toward 9 Mile and go home.

We pulled over on a dark street, between street lights. I turned the car off. For several minutes, it was ideal for talking about heavy subjects.

What we didn’t know was that the Universe dangled us over a fiery pit, because its folly led us unhumorously 14,784 feet (2.8 miles) away from where we started. It ushered us out of Oak Park, eased us through Pleasant Ridge, piloted us past scary Woodward Avenue, and then led us arbitrarily through Huntington Woods.

After dozens of left and right turns, we had arrived just one and one-half blocks the from Huntington Woods police station, only 700 feet from Officer Hurt’s peers. What are the chances?

Unlike Scott, who was petrified of his father, I had no fear of my parents. It’s precisely his trepidation that had taken us through the wealthier neighborhoods because the people who lived there came home sooner, put out their porch lights earlier, and had fewer streetlights to shine on our young, pale faces.

But our strategy was t-boned.

As if destined for disaster, we sat like two suspicious schemers outside some quiet suburban homes who, quite possibly, did look out their window, didn’t like it, and called the police.

It’s also possible that I had my foot on the brake, alerting any passerby that someone in a cream-colored, four-door, Chevy Malibu was loitering.

Since we were parked on a side road that was likely an established route for any Huntington Woods policeman returning to the station, we found our hushed heart-to-heart in the darkness of Kingston Street lit up by red and blue flashing lights.

I didn’t recognize the depth of Scott’s anxiety. It took me decades to understand that any cop who learned his last name — “Hurt” — would have undoubtedly recognized it. Then, the worst of all possible outcomes would still play out: his father would find out.

Scott understood this with full angst that it was inevitable these Huntington Woods cops knew his father, and that his father was going to be pissed.

My mother, on the other hand, was all tired out of any serious parenting, so I rarely faced consequences to adolescent infractions after 8th grade. Parental repercussions were all used up by my older siblings, so I wasn’t scared at all. I was almost curious how this might play out.

I had no inkling, but Scott felt a deep and whole-body dread. His assumption (a fair one) was that they’d call his dad directly, but I had proposed a possibility that they’d let him go home with me and my parent, and maybe Mr. Hurt wouldn’t have to know.

We waited for the officer to approach, as there was no need to give ourselves up until we absolutely had to. He knocked his knuckles on the driver’s side glass. I cranked the window down and looked at the officer.

He ignored his usual questions about licenses, insurance, and registration, and asked, “Are you old enough to drive?”

“No.”

He looked at Scott, who didn’t need any prompting. Scott said, “No.”

“Okay, why don’t you take the keys out, lock it, and hop in my car.”

We did, and 38 seconds later we arrived a block and a half away at the little station. As we entered, there didn’t appear to be anyone else there. Something had alerted the officer on the station radio, so he immediately put us both in a compact holding cell.

“I’ve got to go out on a call,” he said. “You can wait in here until I get back, and then we’ll call your parents.”

It occurred to me years later that the officer may have left us there to make us sweat. This was the 1980s, after all, and there’s a decent chance he was laughing about our cliché crime but needed us to believe it was serious business, so he tossed us in there to stew in our juices.

In the end, there was no legal consequence: not a fine, not a ticket; they merely turned us over to our parents.

The door was closed and locked. It was about 5 feet by 5 feet, padded, with simple padded bench seats around two sides.

Scott sat facing the door. I sat on the side, making jokes that Scott did not find humorous.

“Shut up, man! I am fucked!”

“Dude, seriously?”

“Yes! Your mom’s not a cop! My dad is! He’s going to kill me!”

He was crying, with real tears and red cheeks and all. He was actually slumped over with his elbows on his knees, almost rocking, as if he had been severely traumatized. The situation wasn’t good, I knew, but crying? It made little, if any, sense to me. “C’mon, you might get grounded, but so what? It’ll be over before you know it.”

“My dad’s a cop, man! You don’t know my dad. I am so fucked!”

I kept joking, still unafraid, still clueless. Then I thought it would be funny to sing the lyrics to a song we both liked at the time. We were into the 80’s rock music: The Cars, AC/DC, Van Halen, The Pretenders, and, of course, all the staples from the 60s and 70s, like Zeppelin, Journey, The Who, The Beatles, and so on.

One song that we both knew by heart was by a one-hit wonder Head East, who’s one hit was called “Never Been Any Reason.” It’s a terrible song now, but we’d play it loud, often, and sing the whole thing together. Half the song was the chorus:

“Save my life,

I’m goin’ down for the last time.”

“Save my life

I’m goin’ down for the last time

Woman with the sweet lovin’

Better than a white line

Don’t you know she could

Bring a good feelin’

Ain’t had in such a long time

Save my life

I’m goin’ down for the last time, wow

Save my life

I’m goin’ down for the last time

Save my life

I’m goin’ down for the last time

Save my life

I’m goin’ down for the last time

Save my life

I’m goin’ down for the last time

Save my life

I’m goin’ down for the last time”

— By Head East, 1975 —

I continued singing with a grin on my face:

“Save my life I’m going down for the last time…”. I was hoping to lighten up the situation or cheer up Scott some.

I genuinely thought I’d get him to look up at me and hold back a smile or even laugh.

But Scott didn’t lighten up. He said quietly, “It’s not funny, Flavin.” This time, he wasn’t animated. He didn’t shout or lift his head or talk about how fucked he was. He didn’t change his body’s posture. He kept his elbows on his knees, leaning over with his face in his hands. He said it again, plainly: “It’s not funny, Flavin.”

I got it. Well, I got it enough to shut the hell up.

A few minutes later, the officer opened the door and asked us for our home phone numbers. I gave him mine since it was my mom’s car, and I said Scott was sleeping at my house. I had hoped to take the fall, so to speak, because at the very least, I knew my troubles didn’t match his. He closed and locked the door.

Fifteen minutes later, my Mom picked us up. (I can’t recall how she got there. Did Steve, who was 19 at the time, give her a ride? Did she take a cab?)

Scott and I sat in the back of the car, and I returned to teasing and razzing him.

Mom turned around at the next stop sign, and laid into me: “Just stop! I just left the comfort of my bed to pick you up at the Huntington Woods Police Station at 2:30 in the morning.”

I lost my grin, but in my head I was still cocky about it.

“There is nothing funny about this,” she added, firmly. I’ll bet Scott was relieved.

Decades later, I took a trip back to Michigan, and I saw Scott. I lived in Baltimore at the time, and he joined me and several others for a mini, impromptu reunion at a Como’s Pizza on Woodward and 9 Mile in Ferndale.

So little has changed between Scott and me. It could be years between visits, yet Scott and I jump right back to meaningful conversations. No small talk. Off to the side from others, our little nighttime jaunt in Huntington Woods came up.

I asked him, “Remember I started singing, ‘Save my life, I’m goin’ down for the last time…’ while we were in the cell?” He did. I said, “I was being such a dick, laughing and making jokes while you were just freakin’.”

He said, “There’s something I never told you about that night, and then you went to Seattle, so we never really talked about it again.” Scott paused.

He added: “My dad beat the shit out of me for that.”

I remember him saying in the cell that his dad was “going to kill him,” which I took figuratively of course, but now, I wasn’t sure if he meant “beat the shit out of me” literally or figuratively. I confirmed: “You mean like…”.

“Yeah, like, he beat the shit out of me all the time. That’s why I was so scared. That’s why I didn’t laugh about the song. I knew what I was going home to.”

“So … that was normal?”

“Yeah. He used to hit me and my brothers. They maybe didn’t call my dad that night, which is why I was able to go home with you and yer ma, but knowing my last name, they must’ve called him the next day I’m sure.”

I“You fucker,” I thought. “Why didn’t you tell me about this back then? We shared everything with each other!” I felt like he should have let me know. That was my first emotional reaction, but of course I understood how abuse usually works, and how the abused often hide it.

I did say, “I’m sorry, man. I didn’t know. I had no idea. I’m sorry.”

“Naw, man,” Scott said, “it’s a long time ago now. I’ve figured it out. I’m good.”

I started to dig in a little further, as in, “When did it stop? Did you maintain a relationship with him as an adult? Where is he now?” And so on. But there were others at the gathering, and our conversation shifted to someone else’s world.

While Scott and I sat in the 5 x 5 padded cell, the tragedy wasn’t that he was “goin’ down for the last time”, it was that he was going down for the next time. Something that had happened enough times before that he knew there would be a next.

His body told him so.

I agree with the philosophy that we are who we are because of what we’ve been through. The question, “If you could start your life over at any age, when would it be?” is an interesting exercise in “what if,” but it’s most useful for illustrating how we’ve changed. It’s useful for reconstructing our lives so we can more clearly see who we’ve become and how we got here.

My bullying Matt Ross and others in junior high could have been spent getting to know him. My objectification of girls could have been spent respecting them. My not truly hearing my closest friends could have been spent listening. How might my life and theirs be different if…?

I don’t actually wish I could go back for the simple reason that I can’t go back. I generally don’t spend much time wishing things were different.

So, writing this story is not an exercise in “what if”; rather, it’s an emphasis on what is.

Written December 27, 2022