Artwork by Kirsten Pinkerton | “Night Drive #1” | Mixed Media | Instagram: @redrabbitpainting

I don’t believe we live after we die, but there is the Einstein quote:

“Energy cannot be created or destroyed, it can only be changed from one form to another.”

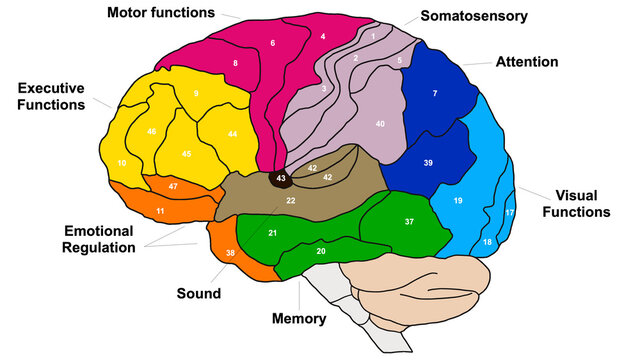

Growing up, my older brother Pete helped me understand abstract concepts. One time, I was just young enough that I couldn’t wrap my head around what it means to think. As a kid whose executive function hadn’t fully developed (I must of been about 7), Pete tried to help out.

“You’re doing it right now,” he said.

“Doing what?”

“Thinking!”

“But what is it?”

“You’re doing it right now!”

It was no good. Pete, about a year-and-a-half older than me, may have been able understand abstract ideas, but he couldn’t explain what thinking was to someone who didn’t know. How does one explain what it means to think? Would it have helped if he offered a definition?

“Thinking is when the brain processes information in order to form thoughts, communicate or take action.”

I doubt it would have helped. As a younger kid without the skills needed to comprehend abstracts like thinking, it probably made no sense to me because I couldn’t feel it. If I blinked or ran or peed, I could feel it. I couldn’t taste it, hear it, or even smell it. I definitely couldn’t see it, and nothing on my body moved, so how could thinking be anything at all?

A few years later, after my brain had caught up to Pete’s, we often had casual, early teenage philosophical conversations. One in particular was about whether or not Einstein’s quote offers clues about whether we live after we die.

We wondered if, as animals and therefore bodies of energy, we must live beyond death. Einstein said so. Of course, we didn’t know, but for many years after that, I had always been open to the possibility that our body’s energy survived as long as the universe, changing from one form to another for billions of years.

Then we faced questions like: Since the body is decaying and the brain is dead, can that changed energy think like we do now? Where does the energy go, and what does it change into? Does that energy maintain our identities, allowing us continue to be conscious of our individual selves? And if so, can we affect the lives of our family and friends who are still alive?

And so on.

I’ve always been fascinated with religion and spirituality and questions of god and the afterworld. My parents raised us to believe whatever we wanted, but dad was a disinterested atheist:

Me: “Dad, do you believe in god?”

Dad: “No.” (Pause) “Let’s go to Duke’s for lunch.”

And if you pressed him on it, he’d get impatient. It was a truly pointless conversation to him.

Mom preached no particular god or religion, but she was open and, on occasion, we’d talk about it. She was agnostic, if I had to guess, despite her mother being a hardened Baptist.

In practice, neither of them showed devotion to a god, so it’s not entirely surprising that I came to the flat and cold conclusion that in 7th grade a deity had nothing to do with my stunning chin-ups victory in the 1979 Best Junior High athletics contest.

And yet, throughout my life, certain inexplicable events have challenged that flat and cold conclusion. There have been a few moments with which I must reckon, despite my dismissal of intervening gods or friendly spirits.

It’s a paradox that I’ve chosen to resolve by not resolving it: whether some of those moments were driven by a god, my dead mother or some other sentient life force not measured by science, or if the strange events were simply enormous coincidences or bizarre turns of events.

After praying for victory in a chin-ups contest in at Best Junior High School, I made up my mind.

1979

At Best, in Oak Park, Michigan, they had a physical fitness contest in which students competed to do the most chin-ups, jump the farthest broad jump, climb the fastest time up and down the gym rope, and others. Eighth graders competed against eighth graders, seventh against seventh, and they posted the winners with a marker on big white sheets of paper in the hallways.

I wanted my name up there for everyone to see. I knew I could compete in my own grade, but Ronnie Rocheleau, who wasn’t a big guy but whose forearms were already bursting with adult-like veins, was the 8th grade champion with 17. Eighth graders had completed their events; 7th graders would finish theirs the next day. I didn’t know how many I could do, but thanks to Rocheleau going first, I had a clear target: 17.

I lied in bed the night before and prayed:

“Dear God: please let me tie Ronnie Rocheleau. Please let me do 17 chin-ups.”

Whatever I had learned about god, I knew not to try to take advantage, so I played it humble.

“God: I’m not asking to do more chin-ups than him; I just wanna do 17.”

I had thought this through, basically trying to outsmart god. After praying, I would tell myself that tying an 8th grader was the same as winning since I was only in 7th grade. I suppose I thought that my desire to be the winner through a tie would be humble enough for god, so he might reward me by answering my prayer and granting me victory.

The next day, I exceeded Ronnie Rocheleau’s number by one: 18 chin-ups.

It was an enormous victory, and I felt pretty good about myself. I didn’t just tie him, I had beat him outright and I was a year younger. It was a double victory, and clearly god had heard my prayer.

A few days later, I was lying in bed again, thinking about how god helped me win. Something about it didn’t sit right. There are a lot of ways for a young person to interpret this, especially considering the immediate fulfillment of my prayer: God thinks I’m special. God wanted me to win. God rewarded me for my determination, etc.

But those were not my conclusions. Instead, it was a transformational moment in which I effectively ceased to have any use for god. I told myself, in so many words:

If god helped me win, then I didn’t really win. He did.

And if god won, then I accomplished nothing. It’s like I cheated.

Therefore, god didn’t help me win. I won. God had nothing to do with it.

At age 12, it was black and white. Either god won, or I did, and that was that. I would believe in science above god for the rest of my life, because I figured that there are billions of people praying every day, and god’s involvement in their lives is no different than mine. Already, my mistrust of an omnipotent being was cementing fast. To me, if there were a god, it either participated in our lives, or not at all, so I had decided that I would not commit myself to a god that plays favorites, even if it meant that I benefitted.

That one prayer and subsequent victory taught me that everything in my life is either earned by me and me alone, or it’s fucked up because I fucked it up.

Despite my parents’ noncommittal views, my inclination to think scientifically, and the transformational event that precluded god from participating in my chin-ups victory (or anything else), a number of apparently supernatural events have plopped themselves into my life, forcing me to wonder:

Is everything so easily explained by physics and other measurables? Is someone or something that transcends this world interacting with us?

Could it be that Einstein’s theory of energy holds the key to the mystery about life after death, and a deceased friend or relative has been looking out for me?

1984

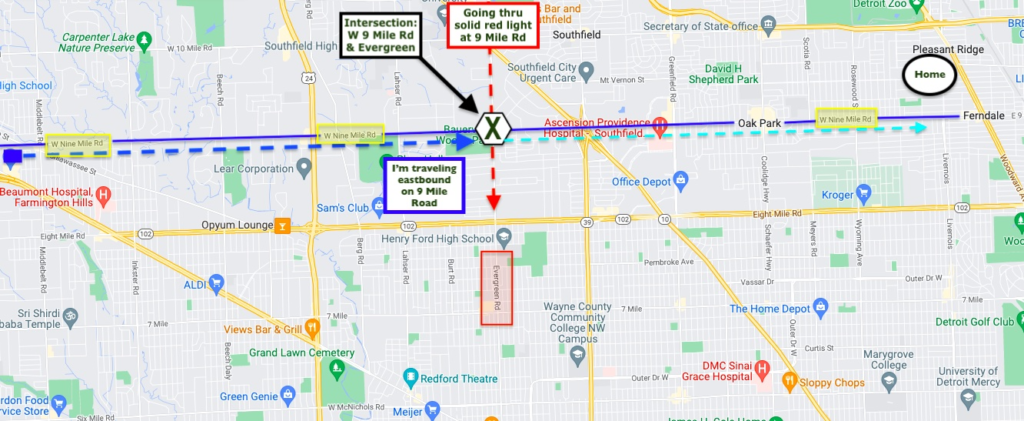

One night, when I was 18 and finishing up my senior year, I was driving home from a girl’s house. Not a girlfriend, no sex that I can remember, and it wasn’t a party, so I wasn’t drinking. Just a female friend from another town. That, in and of itself, was strange for me. I didn’t have too many friends outside my local Ferndale and Pleasant Ridge circles, and I can’t remember who she was. In fact, I don’t think I ever hung out with her after that night. Maybe she actually was a romantic interest, but I wasn’t getting any, so I moved on. In any case, she lived about 12-13 miles away in Farmington (see map), and I left her place close to 3 a.m.

If there’s one thing you learn growing up on Detroit-area streets, it’s that traffic lights are impeccably timed. On major roads, heavy traffic aside, if you leave one light when it turns green and travel at the speed limit, you’ll make the next one green, and so on.

For example, if you leave 8 Mile Road driving northbound on Woodward Avenue and travel the speed limit, you’ll make it to 14 Mile Road and beyond without stopping once for a red light, passing gleefully across a dozen or so major intersections through wide open green lights. Going the speed limit has never been so satisfying.

Everyone in Detroit knew this, even kids who just got their driver’s license, like me. I was in my turquoise ‘69 Buick Gran Sport traveling eastbound on 9 Mile Rd and got into the groove, which was easy to do because it was so late in the night.

I made the first light at Orchard Lake Road, then Middlebelt, then Inkster, and then Beech Road. I still had a half-dozen more lights to go.

All of these roads are exactly one mile apart. Every minute and 22 seconds, I crossed a major intersection and, in between, I was lulled by a mesmerizing rhythm of street lights, so I had developed a rather hypnotic tempo that effectively made me less conscious of my driving.

Then came Telegraph, then Lahser. I was on auto-pilot but awake and sober. It was well after bar-closing time, so there were almost no cars on the road. I had set my mind and my foot to 45 mph and utilized the Oakland County transportation management system exactly as intended.

And then came Evergreen Road.

Like the last six intersections, Evergreen was a major thoroughfare with a 45 mph speed limit. As I approached, I had the green light as promised, and for some reason, I lifted my foot from the gas pedal. My car gradually slowed, and as a response, I looked up to see why I was slowing, as if I weren’t responsible for doing so. Reflexively, I pressed the brake lightly, just enough to slow down a little more.

Now, traveling about 35 mph, a car on Evergreen went straight through the red light, right where I would have been had I not slowed. Speeding, or so it seemed, the driver showed no sign of even knowing that he was running a red light. Either s/he was plastered or high or they had seen the empty roads and decided the risk/loss benefit was on their side.

It wasn’t. I should have been in front of that car.

Contrary to my mathematical understanding of the traffic lights, despite my driving consciousness being temporarily suspended, and even though my mind was free to think about virtually anything else, I slowed, and it saved my life. It made no sense. I would have crossed at exactly the moment that car would have turned me, my Buick, and my entire life upside down.

After watching the car fly past at no less than 45 mph, I saw no cars in my rear-view mirror, so I slowed even more and coasted through the intersection at about 15 mph, looking both ways blurrily with tears in my eyes. Not a car in sight

I was about to be maimed or dead, and instead, I safely crossed Evergreen Road and went home, suddenly very conscious of every detail.

But why did this happen? If god didn’t help me beat Ronnie Rocheleau in 1979, why show up in 1984 as I drove home in the middle of the night? I didn’t know the answer, but I couldn’t settle for the “shit happens” explanation because the intervention felt so blatant. In that moment, I knew my life had been saved by a force outside of myself, and it went against everything I believed.

My sixth sense is whatever, I don’t believe in dumb luck or guardian angels or god, and to this day, I have chosen not to commit to a supernatural explanation, nor can I cancel out the possibility. I abstain, I guess, because believing that I was at the center of a mystical, otherworldly event designed to save my life — even once — seems a little self-important. Why me?

Why would I have slowed down, and yet every day, all around the world, tens of thousands of people are t-boned into tomorrow. Dozens of broken bones, permanent brain damage, paralysis or dead on arrival, ready for the Einsteinian transformation into a new energy.

Why them and not me?

I can’t deny the tears that streamed from my eyes following the inexplicable physical movement of lifting my foot at just the right moment; I’m alive today because of it. Ten miles of intersections, and I slowed down at the only one that would have killed me had I not done so.

Do people have a sixth sense that predicts disaster?

Was it a sentient being gently lifting my leg’s weight from the gas pedal, like a guardian angel?

Was it dumb luck?

Was it fate, a so-called “plan” that keeps people alive or demolishes their bodies because everything happens for a reason?

Was it God, with a capital G, working in mysterious ways?

I didn’t know, but something happened that night. I still don’t know, but something happened that night.

I have always been noncommittal because believing in something supernatural just one time automatically pledges me to something omnipotent on an everyday basis. I’m not ready for that.

Instead, I’ll stick with the less interesting, more provable ideas that we create our own luck (good or bad), guardian angels are wishful thinking, fate will do whatever she damn well pleases, and gods don’t intervene to save anyone’s life, nor are they thoughtful enough to make me the Best Junior High chin-ups champion of 1979 while ignoring Ronnie Rocheleau and his impressive, vein-encrusted forearms.

And yet, I still have no explanation for that night on 9 Mile Road and Evergreen.

Written March 25, 2020