Either because my father wanted to be with other women or because she was depressed, my parents got divorced. One led to the other, but it’s unclear to me which came first. I only know that their marriage’s demise after 23 years involved my dad’s narcissism, the social norm of the 1960s that a wife owes her husband a pair of open legs, my mother’s resulting despondence, and the absence of the eyes of God to damn such a decision.

Or, after 23 years, divorce was a reasonable consequence of raising five children in a 935 square-foot house with one bathroom.

The year was 1974, and it was like a bomb had dropped on our home. The same year my father moved out, my sister — then 16 and set on pursuing her independence — left Michigan for Simon’s Rock’s Early College in Massachusetts. Paul, 15, had quit high school to spend his days and nights being high or drunk with friends in their late teens.

The household had gone from crowded to roomy. From seven to four. I was eight.

Before Liz left, I remember peeking down the stairs to see her seated at the bottom and my mother trying to reason with her. I didn’t hear a word, just somber notes broadcasted for anyone within earshot. I’m sure they talked about how Liz was going to survive 700 miles away on her own at 16.

Conversely, she couldn’t always reason with Paul: “That’s what happens when you smoke pot!” she would yell, as he lay in his own vomit on the avocado green tile in the basement. Of course, it took me twenty years to realize pot never made Paul throw up — he had alcohol to thank for that. And it took another twenty years to find out my mother smoked pot only a few years before she admonished him so vehemently. Was she trying to dissuade us younger boys from smoking pot? If so, it worked. At eight, listening to her voice, it was traumatic enough to scare me straight, and I was anti-pot throughout all of high school and a few years after that.

But I remember her words. I remember her anger. I remember the fire my mother still had in trying to salvage what was her family ripping in half.

Mom’s perspective: Five children, two miscarriages, 935 square feet. Seven people. Three bedrooms. One toilet. Two bunk beds in a silverfish-infested basement. A furnace so big it required its own room. A divorce and two child-exoduses.

From 1958 to 1974, my mother and father pulled off the parenting gig despite ridiculous circumstances, and their marriage prevailed for twenty-three years in all. On some level, that has to be admired.

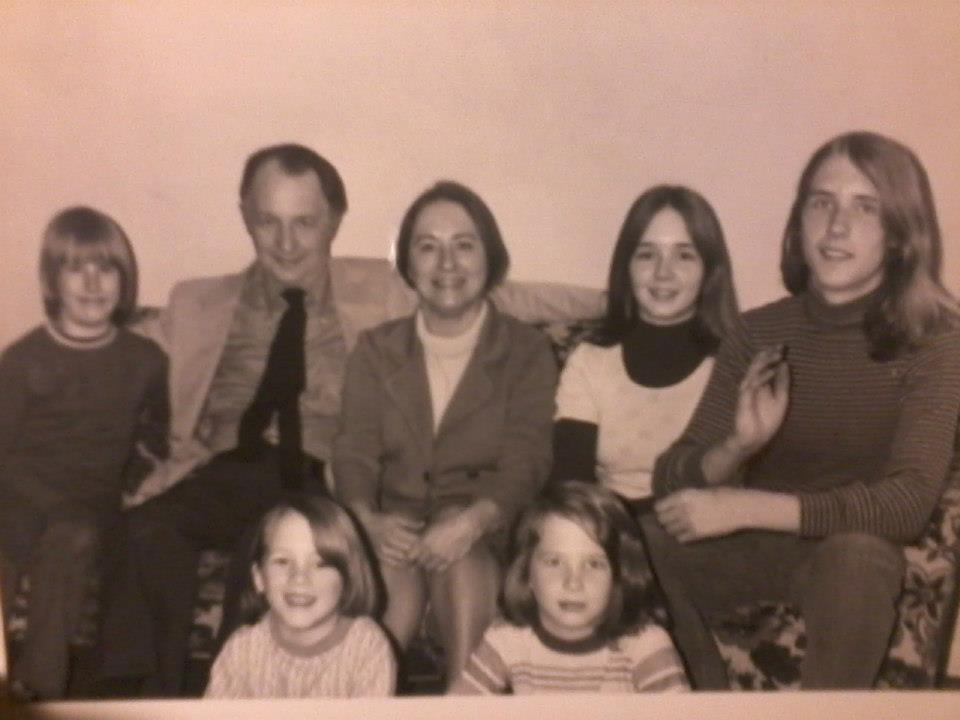

The Flavin Family, 1973.

Left to right: Stephen, 10; Dad; Mom; Elizabeth, 14; Paul, 13. On the floor: me, 6; and Peter, 7.

Nevertheless, 1974 left us a family of four; the oldest boy, Stephen, was 12. He tried venerably to help mom manage. He made rules: “You can only have one bowl of cereal!” He commanded. “Only three cookies at a time!” Mom’s rule, but he was the enforcer. He had a rule to help limit the cost of utilities, keenly aware of our mom’s challenges given my dad’s paltry court-appointed $68 a month child support: “No, your friend Mike can’t shower; what is this, a Holiday Inn?” We laughed for years about that, although Steve was dead serious at the time. He was cantankerous for many reasons as he tried to keep the pieces together while still a child himself.

Regardless, my mother fitted us with quality athletic shoes, saved money, took us on trips to Granddaddy’s self-built house in Kentucky, and she fed us well while toggling between welfare and a low-paying copy-editing job with Ford Motor Company. She sat at the bottom of their hiring list for years: first to be laid off, first to be hired back.

This Great Depression-era woman, whose smile and respect extended to every person she met, had many good days of course. But the Flavin family story isn’t a comedy or tragedy in the Shakespearian sense that it ends well–or doesn’t. It isn’t a heroic journey either, as in Odysseus being the last man standing. It’s about the reality that life will do whatever it damn well pleases: pay attention. What happened to each of us in the next 50+ years depended on how well we paid attention.

My mother’s family around 1934, in the middle of the Great Depression: the Lanes from Clay, Kentucky.

Left to right: Betty, Louise, Barbara, Tom, and my mother, Jeanette.

By the time my mother mothered me, the youngest, she was all mothered out. When she found out I drank alcohol at the same age that she was shouting down the stairs at Paul, 15, she voiced a simple question, both sincere and mildly incredulous: “Why do you drink?”

I probably projected her tone of disbelief, but I distinctly remember her voice was calm and sincere. It was a timeless Oak Park summer day, and her straightforwardness left me short of answers.

“I don’t know,” I all but whispered. She said nothing.

She remained silent, forcing me to give some kind of answer: “To be happy?” I guessed, avoiding eye contact and fiddling with blades of grass between the strips of the sun-soaked cement that made up our driveway.

“You’re not happy?” she asked. Mom knew it was the second-most useless answer following “I don’t know.” Still seated with her gardening gloves on, she turned and pulled weeds from her tomato garden.

She was worn by life, yes, which explained her passive approach to the news that I was drinking at the age of 15; she was also too kind to say that my responses were horseshit, which, had she the energy, would have been her exact words.

I can’t remember how that conversation ended. That is, I don’t know how I managed to get out of it untouched by even a morsel of admonishment. No tsk-tsk, no finger-wagging, no adult-to-child reprimands, and no projectiles of shame from her ill-persuaded eyes. Still, or maybe because of that, it left a lasting reminder — like a little yellow flag suction-cupped to my forehead: pay attention.

I have occasionally applied this stroke of genius to future scenarios and other risky decisions. Because of that little yellow flag, I’m alive and well today, despite many acts of stupidity. The simplicity of her question, “Why do you drink?”, the calm in her voice, and the acceptance in her eyes guided my focus on the world as I entered adulthood without her, or any role model, for that matter.

That was 1982. She died a year later from lung cancer, two years after she quit smoking Kent cigarettes because a “shadow” showed up in an x-ray. It was too late. Age 53, smoked for 35 of them. That yellow marker hangs down in front of my eyes, but for many years, I carried the burden of choosing to be late to see her one more time before she said good night to the world.

On March 25, 1983, my brother Steve received a phone call from the hospital, warning us that she may die any minute. Steve is the brother who grew up in hurry, and at this point, all of our previous contention over the number of bowls of cereal we could eat, or who could shower or not, washed away like sidewalk chalk art on a rainy day.

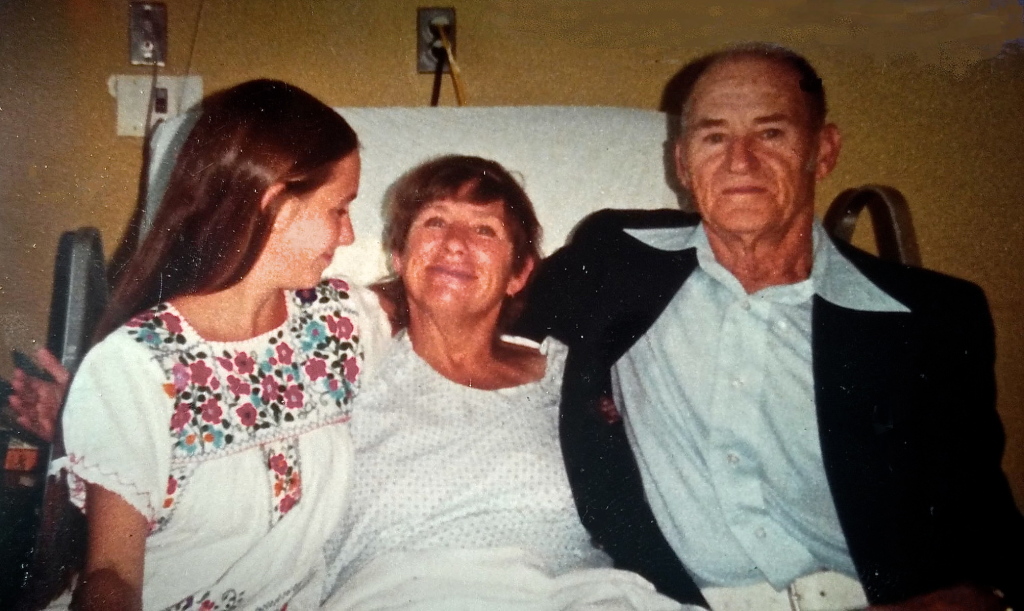

The hospital, 1983, the year my mother died.

Elizabeth, 25; Grandaddy, 80

I slept in the basement. Steve said, “John.” I didn’t respond. “John, the hospital said we may want to visit mom.”

“John,” he called again, as if trying to wake me. “John,” he called again, gently, a little louder.

I heard him the first time, and the second and third.

“What?”

“Mom might go tonight, the hospital said. Do you want to go with me to see her?” I laid on my right side, one sheet and a thin blanket covering me, and I thought for a few moments without a sound. What was there to think about? Why did Steve even ask? Why wouldn’t I go?

“No.”

“Are you sure?” Another several moments passed. Steve knew when to be patient.

“Yes, I’m sure.”

It was midnight, and he left. I heard the front door latch firmly with its distinctive solid metal sound that one doesn’t hear in modern doors. I told myself, inexplicably: I can go tomorrow—suddenly practical—it’s late after all, why would we go tonight when we could go tomorrow?

Steve went to the hospital, and he wrote about it:

“I drove south on I-75, listening to Simon & Garfunkel’s ‘Sounds of Silence’ playing on the radio. It must have been close to midnight as I took the exit to the hospital, and the words, “…Silence like a cancer grows…” bore deep, the timing seeming to mock me. I used the emergency entrance due to the lateness of the hour and a hush fell over the nurse’s station. Everything stopped, including most of the background noise that comes with their activities.I expected the worst at that point; they all knew why I was there, one of them stepped forward to point me to the room. I thought that I was prepared but realized upon entering that I was not—she still had perspiration on her face. I had just missed her. It felt like my life energy had been instantly sucked from my body, my knees buckled, and I immediately began sobbing. Going to her bedside, falling on her, gasping for air, all the anxiety and worry of the last seven months erupting in a few moments. I have no idea how long I was in there. Thinking back now, I wish I’d had a hankie to wipe her face.”

He was too late by minutes. Maybe seconds.

There’s no getting around it: it was stupid not to go. I suppose in the dark basement I couldn’t see the little yellow suction-cupped flag.

Now I’m 44 years old. Life always seems to be ahead of me, and so excellent decision-making always seems to be around the bend. Somewhere up there. The secret, I think, is to make the decision in the moment—in the moment—because life doesn’t need a few years to leave you behind, sometimes it only takes a few seconds.

2022 Post-script:

I look back on the dozens of near-misses and prancing around land mines, in search of sound judgment. That’s what’s familiar: the chasing. But mom staked that critical little yellow flag out there ahead of me a year before being diagnosed with terminal cancer. Later, every so often, a friend or brother or sister or stranger laid down another yellow marker until, a few decades later, I can now see the path of little yellow flags behind me, leading right up to this day.

I see myself careening off stupidity, floating on clouds of grandiosity, stumbling over narcissism, and plodding around in self-loathing. I can see the blood at my feet from naively running into stone walls I thought I could bust; I can see my staggered footprints after I ran out of control, my momentum carrying me toward the cliff’s edge, stopping only inches from disaster.

Was it mom’s little yellow flag hanging down in front of me that allowed me to avert tragedy? Or did fate pull those reins? Was it dumb luck?

Regardless, I paid attention, but it wasn’t always pretty.

Written March 25, 2010